I read a quote the other day by Bengali Nobel Laureate, Rabindranath Tagore:

“I slept and dreamt that life was joy.

I awoke and saw that life was service.

I acted and behold, service was joy.”

I saw article in the Guardian on a barber from Pakistan who saves lost children. He lives the poem.

Pakistan's unlikely crime fighter

How has a poor, uneducated man gone from cutting hair to rescuing a legion of lost and kidnapped children? Meet the Barber of Larkana…

- guardian.co.uk,

| ||||||

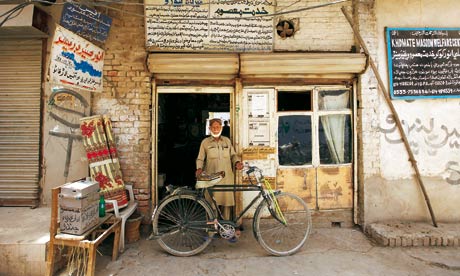

| 'Hope should never be lost': Anwar Khokhar, the Barber of Larkana. Photograph: Charla Jones for the Guardian |

The gravedigger spotted the bundle lying behind broken gravestones in the old Christian cemetery in Larkana. At first he thought it was a pile of sacks, but when he saw the dogs gathering, he decided someone who could not afford burial rights had dumped a body. Then a teenager poked out her head. Taking in her shaking, skeletal frame, the gravedigger worried that if he didn't do something immediately, he'd soon be digging another hole. He lifted the girl into his arms and stared into her face. The scorching sun burnishes everyone's skin in Pakistan's deep south, and this girl was fair. Her pale complexion hinted at a well-bred family from which she'd run or become separated. Holes ran the length of both ears, suggesting that she had once worn elaborate gold jewellery. Those days were clearly gone, but there was no way to find out why, as the girl was mute.

Across Pakistan, an unknown number of children, thought to be tens of thousands, have been kidnapped by ruthless bandits, or "dacoits", who see their ransoms as easy money. It's a growing problem, particularly in the southern province of Sindh. In feudal Larkana, where hereditary landlords control vast swaths of fertile land that the tenanted poor cultivate with watermelons, rice, guava and sugar cane, central government in Islamabad is practically inaudible; the air-conditioned marble halls of the capital 750 miles to the north may as well be in another country. Murderers and extortionists hunt the more affluent streets and markets for children to abduct, in increasingly savage kidnappings, and it can seem as if local law-makers are powerless to prevent it.

Not a month passes without another grim discovery: an eight-year-old is found dead on the tracks behind the railway station, mutilated by criminals getting back at a family unable or unwilling to meet its demands; the charred remains of two sisters who had fled the Taliban in the country's north-west, only to end up in the hands of Sindhi crime lords. The girl in the graveyard was lucky to be alive. Examining her, doctors concluded she had been kept prisoner for many months and probably gang-raped. Then they handed the nameless, speechless girl over to Anwar Khokhar, a barber who, for 20 years, has been helping Pakistan's lost children – searching for the kidnapped, fetching wanderers back to their parents and sheltering the bewildered. This unlikely crime fighter is now known to all as the Barber of Larkana.

In the stifling interior of Sindh, the Taliban and al-Qaida have little presence. Many locals talk proudly of religious tolerance, pointing out how, in the lanes and watermelon fields, green-painted Sunni mosques sit side-by-side with a multitude of poles bearing the black flag of a Shia household. However, the authorities in this desert city are still nervous about foreign visitors. An armed guard sleeps outside our hotel room, and if we travel any distance out of town, a police pick-up leads the way, while another guards the rear, filled with officers cradling assault rifles. Even our Karachi driver is afraid to make unplanned stops in the countryside, refusing point-blank to do any night work, terrified of Sindh's notorious dacoits. But not the Barber of Larkana. His city centre shop, hung with its 50s photographs of child models sporting a multitude of short back and sides, is open, unguarded, doing a steady trade. Two old reclining chairs sit before a wall of mirrors, towels and prayer cards beside them. At the centre is Khokhar himself, a trim 70-year-old, dressed in a simple olive kurta, his pockets stuffed with scraps of paper: leaflets about missing children, rupee bills, bank account details that he hands out to potential backers. A tatty, sequined cap sits on his head and on one finger he sports a great glass ring like a boiled sweet.

The barber points above the mirrors to where a collection of photographs hints at how a poor, uneducated man went from cutting hair to tracking a legion of lost children. In pride of place is a cluster of signed photos of the Bhutto dynasty, Zulfikar, his daughter Benazir and her two dead brothers, Shahnawaz and Murtaza. The small, unprepossessing village of Naudero, 20 miles beyond the Larkana city limit, is the childhood home of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, former prime minister and president of Pakistan. Bhutto was born in this village and is buried in its mausoleum. It was here, too, that the body of Benazir Bhutto was brought in December 2007 after she was assassinated, her remains placed between her father's and those of her brothers.

These days, Naudero is a pilgrimage site for those who champion Bilawal Bhutto – the son of Benazir and Asif Ali Zadari, Pakistan's president – an heir-in-waiting, currently completing his studies at Oxford. Although he lives more than 4,000 miles away, his face is plastered on every street corner and graffiti spells out "BLO", the Bilawal Lovers Organisation, a fanclub and Facebook page that is counting the days to his return. Even as a child, Khokhar sensed that finding a personal link between his family and the rising Bhutto dynasty might make all the difference. He was born during the "great floods of 1942"; by the time he was six, his father and older brother were dead from curable diseases. He was married at 14, to his 10-year-old first cousin, and by his early 20s was well on the way to having eight children. He moved his family to Larkana, where he began barbering and joined the new Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) of the fast-rising Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. He cut hair and attended PPP rallies in Jinnah Park, spending the evenings researching his family.

When he came across a line of relatives from Naudero, it gave him the foothold he needed. "Eventually I secured an invitation to cut the great leader's hair, just after Bhutto became prime minister in 1973. I was led into an office that was piled high with files," he says. "Mr Bhutto looked up from behind the desk. I said, 'Sir, do you want your hair cut short or just a trim?' He replied, 'It's your decision, just make me smart', and went back to his paperwork." A few minutes later, Bhutto looked up again to find the barber frozen, scissors in one hand, Bhutto's nose in the other. "Mr Bhutto asked, 'Why are you shivering?' I replied, 'Because you are the prime minister of Pakistan, sir, and I have you by the nose.'"

The barber became a fixture. "The Bhuttos respected me and knew I wasn't greedy," he says, pulling out a cheque, signed by Zulfikar, for 2,000 rupees (then worth £34), which he decided to keep as a memento. The relationship blossomed. By the time of Benazir's first premiership in 1988, Khokhar's link to Pakistan's first family had worked out well for him. He now had his own barbershop, opposite the brightly painted Qaim Shah Bukhari shrine on VIP Road in Larkana. Aside from barbering, Khokhar often volunteered at the shrine – work that brought him into contact with stray children and runaways. At first he would simply broadcast their names over the loudspeaker. "Then I bought a brass bell and began to tour Larkana, holding the hands of lost kids, trying to get parents to come out of their homes," he recalls. "Sometimes the child would be too tired to walk, so I would strap them to my waist or carry them on my shoulders."

Eventually, so many children began streaming to him – some lost, some escaped from the increasingly powerful criminal gangs – that he bought a tricycle and made a platform above the rear wheels for them to ride on. "In the evenings, if the parents had not been found, I would take them home to my wife." When Husna Khokhar complained that she already had eight children to feed, the barber persuaded a local PPP politician to donate a piece of wasteland on Airport Road, a mile outside the city, where he built a shelter. It would take him three months to draw a name out of the mystery girl from the graveyard: Aleesha. It meant protected by God, but whatever had happened to her had left her doubly incontinent. After one week at the shelter, she began to eat tiny slivers of rice chapatti cooked by Husna Khokhar, and a mouthful of daal. After two weeks, she began to dance, a strange circular motion no Sindhi recognised. The barber put her photo in the paper. No one came forward. She was featured on local television. No response. Soon after, she began reciting the Qur'an, word-perfect from memory. "We thought she must be from a wealthy Sunni family," Husna Khokhar suggested, dreaming of a large reward, until Aleesha began beating her chest and reciting what sounded like a Shia prayer, too. Six months ago, she clammed up altogether. Today, she is sitting blurting out a name: "Ali Ghulab, Ali Ghulab." The barber wonders if it was her father. His wife smiles. "It's a boyfriend," she says. Aleesha responds: "I love Ali Ghulab" and a smile spreads across her face. Then she grabs a notebook and starts writing feverishly, from right to left, meticulously applying all the points and accents above and below a delicate, flowing script that looks like Urdu. It is written in a style that would suggest she was well educated. But nobody here can decipher it. When she begins to sing, the room falls silent. Here, briefly, is a glimpse of the person she once was. Khokhar rises, frustrated. He takes us into his records room, wanting to show that not all his cases are so tricky. The room is filled with a gigantic stack of well-worn exercise books, page after page containing passport-sized photographs and newspaper announcements about the abducted, lost and found. Here, too, are the inky thumbprints of a multitude of grateful parents. Some were reunited within hours; other cases took years.

In a country of 170 million, where natural disasters, conflict, suicide bombings and mass migration occur all too frequently, no one has the time or resources to collect accurate statistics on disappearing children. However, what the barber will tell anyone who asks is that the sheer size of the population, overwhelming poverty, failing infrastructure and weak government mean Pakistan is a hard country to survive for the young. We flick through his current register, nine missing children reunited with their families in the first week of May. The previous month, 23 boys and 18 girls were handed over to their parents, including five-year-old Shahid Hussain, case number 8,855, who had wandered off from his home in Zulfikar Bagh.

Khokhar's attention is drawn by a phone inquiry about a four-year-old brought in that morning. While he's talking, another long-term resident wanders in. Wearing a pink paisley shalwar kameez, her hair in pigtails, she says her name is Kiran and that she is 10. Her voice sounds much younger and the barber, when he gets off the phone, agrees. "I've been trying to identify her since January 2007, when police found her wandering around Larkana railway station, disoriented and distressed," he says.

She is desperate to go home, having watched hundreds of other children pass through the blue gates during the four years she has been here. "We have placed her photo in the paper and on Kawish Television News so many times, but no one recognises her." He sighs and reaches out to hug her, but she pulls away. "Can I call my parents?" she says, as though they are just down the road. Where are they? "Sukkur," she says, naming a city 60 miles to the south-west. "Each day it's somewhere else," the barber says. He has driven the length of the province, following the girl's suggestions, with no success. His wife, wrestling with her plump, two-year-old twin grandsons, pipes up: "She also told me her father grew watermelons, but so do millions of Sindhis."

There's a flurry at the gate as deputy superintendent Fida Hussain Chandio of the city police arrives. "We have a big kidnapping problem with criminal gangs seeing kids as easy money," Chandio says. "We try to arrest the criminals. I am a good interrogator. I tortured one man for several hours until he spilled. But there are things we police cannot do; that children will only admit to an old man, like Uncle here." He points to the barber. But it's not just that, he says: "Thousands of people are stepping on and off buses and trains in Larkana every day, and in the process families often lose their kids." As if to prove his point, relatives turn up of a four-year-old the barber has taken in this morning. A man who claims to be the boy's uncle puts his thumbprint in the register and provides a copy of his national identity card before leaving with the child. The barber puts a large tick beside the child's name in his register. "Another success story."

Chandio takes us to the police station. Their most recent case is Mudassir, a wriggly three-year-old, now sipping a Coke on his father's knee in the 48-degree heat. He was seized from outside the family shop in Larkana's main market. Chandio explains how the gang, seeing the queues outside it, had deduced that its owner was wealthy. Habibullah Sher, the boy's father, says: "As soon as we knew he was gone, I went straight to the barber with a photo." Three days later, he received a call. "The criminals said to me, 'Your child is with us, if you want him back you'll have to pay 50 lakh rupees [£36,000].'" Habibullah demanded evidence. The following day, when he went to Jinnah Park, as instructed, he found his son's clothes under a bush, covered in blood.

He contacted the police, who advised him to keep the kidnappers talking while they traced the call. "The kidnappers were threatening me that if I didn't agree to the terms, they would sell him in another province." After three days, the DSP's men traced the mobile phone to a house in Shahdadkot, a town 30 miles to the north-west. Mudassir was recovered, unconscious. He had been injected with sedatives to stop him crying. While Chandio is narrating the case, Anwar Khokhar contemplates a poster announcing a 50,000 rupees (£360) reward for information about missing Sufyan, a four-year-old kidnapped from his home in Sahiwal, a city in Punjab province, four months earlier. "He is likely dead by now," he whispers.

Back at the refuge on Airport Road, we flick through more newspaper clippings. "This was the hardest case to crack," the barber says, pointing to the photograph of a 14-year-old girl wearing an acid green dupatta. "Rashida," he says. Police brought her in seven years ago, saying she had fled her native village after her mother had been accused of infidelity and subjected to karo-kari, or honour killing. "The case against the mother was completely unproven, but the girl told us her father had urged her to run otherwise she would be killed, too." Rashida had been found wandering around Larkana railway station. "We kept putting her picture in the papers and on television," the barber says. In September 2009, he tried one more time. "Her brother finally saw and, after all this time, came to claim her. He said that for the past seven years their father had become mentally sick after losing his wife and then daughter. That case proved to me that hope should never be lost."

He points to another story that demonstrates how easy it is to get lost in Pakistan. He found one girl wandering around his own neighbourhood in November 2009. After establishing her name was Waheeda Sher, he was able to match the case with a missing child report from six months earlier. "The mother had moved here to work as a maid and brought her daughter. One day she got bored and took a walk. In minutes she was confused. After many months, the mother saw her daughter on the local TV station and came to claim her." His wife chips in. "I am a mother, I have strong feelings about children who have been separated," she says. Just as she is telling us that the only cases she urges her husband to steer clear of are the arranged marriage disputes, Naina, a beautiful 16-year-old, arrives. She has run away from Karachi. "My mother is dead," she says. "My father is struggling to make ends meet with seven daughters and one son." Naina's father and several siblings work in a garment factory, making clothes for export to the UK. She was expecting to join them after leaving school, until 10 days ago, when her father announced she was to be married to a wealthy family friend looking for a second wife. "He was old, my father's age," Naina says, eyes rooted to the floor. The night before the wedding, Naina fled with 1,500 rupees (£11) in her pocket, boarding the night bus to Larkana, having read about the barber in a newspaper.

"Her decision to leave has cost the family its honour," the barber says, reaching for his mobile phone to call Chandio. "They will certainly try to kill her. Who knows what will happen if they trace her here." An armed guard will have to be placed outside. Naina seems unconcerned, chatting about a half-baked plan to transform the ground floor of the shelter into a beauty parlour. "Girls can be strong and they have every right to live their own life," she says.

Anwar Khokhar is worried. He has only a few days to work out a solution before the family finds her. He says he'll apply to the court for legal custody: "Sometimes it works and the families promise to behave. But others promise everything and still they will try to kill her." He looks doubtful. "After retirement, people usually grow a beard and sit in a corner of the mosque to please God," he says. "But I believe that to serve humanity is the biggest way to please God. I cannot retire."

• The Khidmat-e-Masoom Centre is at Moenjodaro Airport Rd, Larkana, Pakistan, 00-92-74-4056599.

No comments:

Post a Comment